How Taxing Employment Harms Domestic Labor Markets

What the new H-1B tax means for jobs, wages, and innovation

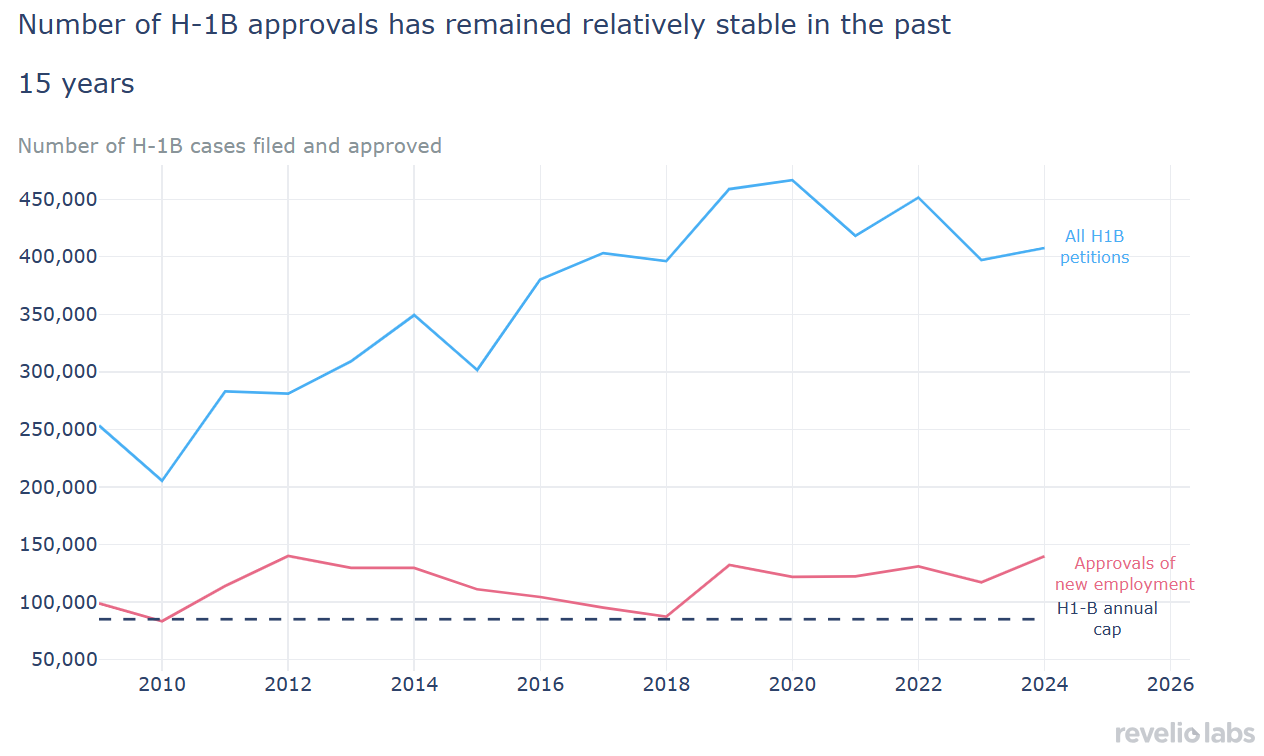

The H-1B program is the main pathway to hire foreign workers in specialty occupations in the US. The program has been subject to a cap of 85,000 occupations since 1990, but approvals exceed the cap due to the uncapped H-1B approvals granted to not-for-profit organizations. The largest share of H-1B petitions is for workers in tech-related occupations.

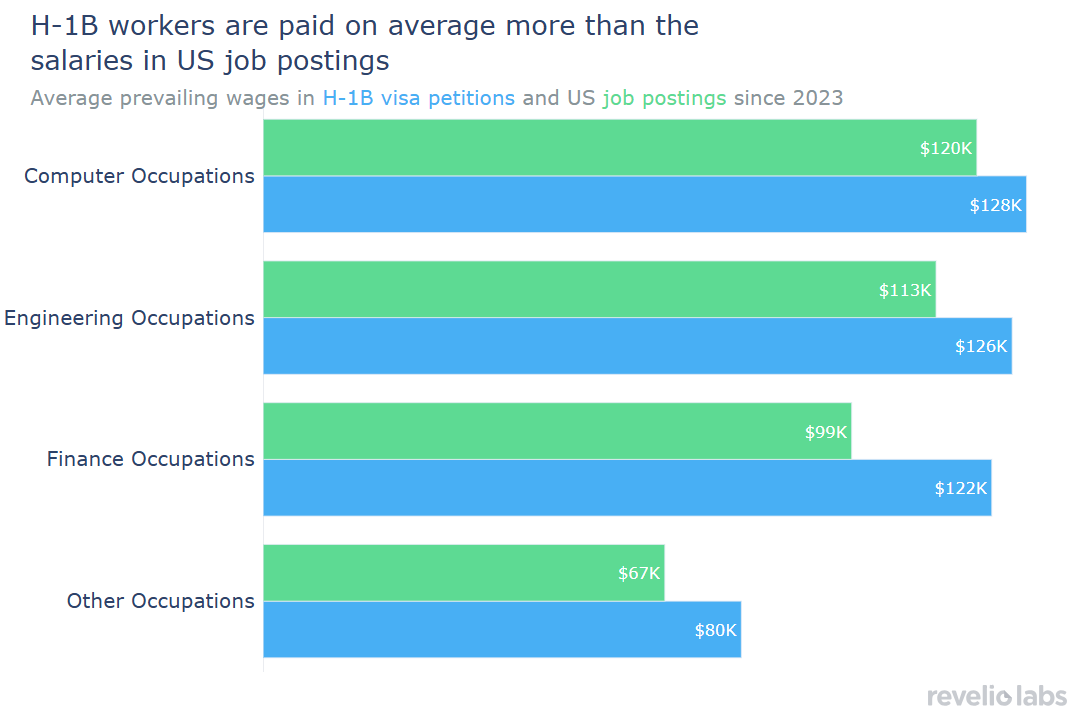

Across all occupations, H-1B salaries are higher than comparable U.S. job postings, reflecting competitive wage dynamics for skilled foreign talent.

The H-1B system is in need of major reforms. However, the $100,000 fee is not a reform in the right direction. It acts as a distortionary tax on employment that dramatically increases labor costs, disproportionately hurting startups and small companies. The fee threatens to hurt the domestic labor market and risks reducing U.S. innovation and global competitiveness rather than creating more opportunities for American workers.

On September 19, 2025, President Trump unveiled a sweeping overhaul of the H-1B visa program, centered on a new $100,000 fee tied to new petitions, presenting an abrupt shift with immediate implications for talent pipelines and hiring plans. After initial mixed signals about whether the charge would recur annually, the White House clarified over the weekend that it is a one-time fee that does not apply to current H-1B holders or renewals.

The H-1B visa is a non-immigrant visa that allows U.S. employers to temporarily hire foreign workers in specialty occupations, typically in technology, engineering, science and other fields requiring a bachelor’s degree or higher. The program was introduced in 1990 to help U.S. companies fill skill gaps in high-demand industries. Each year, the U.S. government issues a maximum of 85,000 new H-1B visas, including 20,000 set aside for applicants with a U.S. master’s degree or higher. Because the number of applications typically exceeds this cap, a lottery system randomly selects the petitions eligible for processing. In addition to the 85,000 visas, the not-for-profit sector is also able to grant an uncapped number of H-1B visas. Over the years, the H-1B visa has become a key pathway, one of very few, for international talent to work in the country. The program has sparked debates over its impact on domestic wages and job opportunities for U.S. workers.

At Revelio Labs, we collect, standardize, and enhance Labor Certification and H-1B filing data from the Department of Labor (DOL) and US Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), which serve as key inputs in many of our models. Our dataset includes detailed information on employers who submit the petitions, job titles, locations, and salaries. This week, we're using this data to take a closer look at the H-1B system to address some of the most immediate questions: What does this new tax on employment mean to the economy? And what downstream implications do we expect?

Despite the annual cap of 85,000 visas, which hasn’t changed since the program’s inception in 1990, the number of H-1B filings grew steadily over time. However, not all applications are for new employment, the category directly affected by the new fee. Many are for renewal of existing H-1B status, change of employer, or other status adjustments. H-1B applications for new employment accounted for 30 - 35% of the total, and in recent years a larger share of these applications has been approved as USCIS changed the application process so that employers can only submit H-1B petitions for employees selected in the lottery system. It is also important to note that the number of approved applications for new employment far exceeds the 85,000 cap. In 2024, for example, 140,000 new employment applications were approved1.6 times the official limit. This is because non-capped H-1B visas are granted to not-for-profit institutions in the U.S., which provide a major path for hiring non-US university professors and researchers. As of this writing, it remains unclear whether not-for-profit institutions are subject to the increase in fees or not.

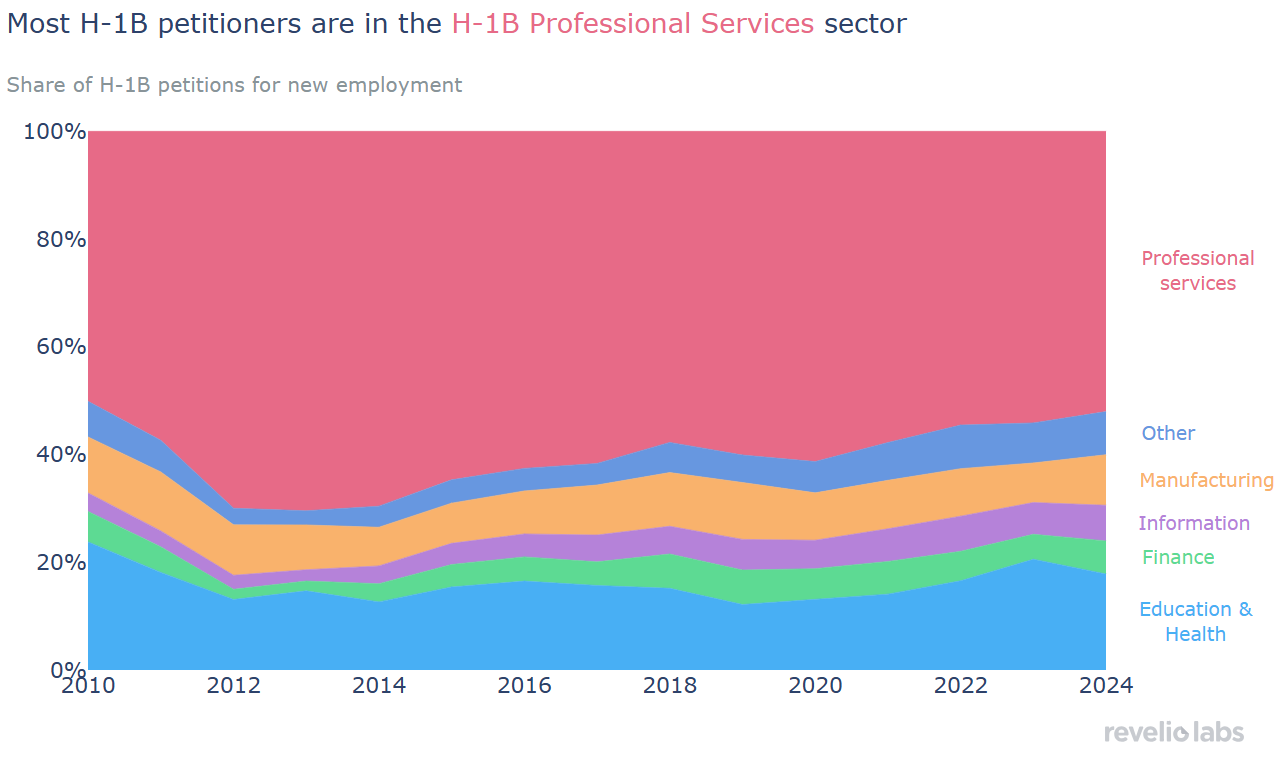

Looking at the distribution of H-1B applications by sector, the Professional and Business Services sector continues to hold the largest share by far. Its dominance, however, has slightly declined since the mid-2010s, while the Information and Financial Services sectors have grown their share of applicants. This shift likely reflects broader changes in the U.S. economy: The rapid expansion of the tech industry, particularly software and cloud services, has increased the demand for highly skilled workers in the information sector. Similarly, financial services have increasingly relied on specialized roles in data analytics, fintech, and quantitative research, which often draw talent from abroad.

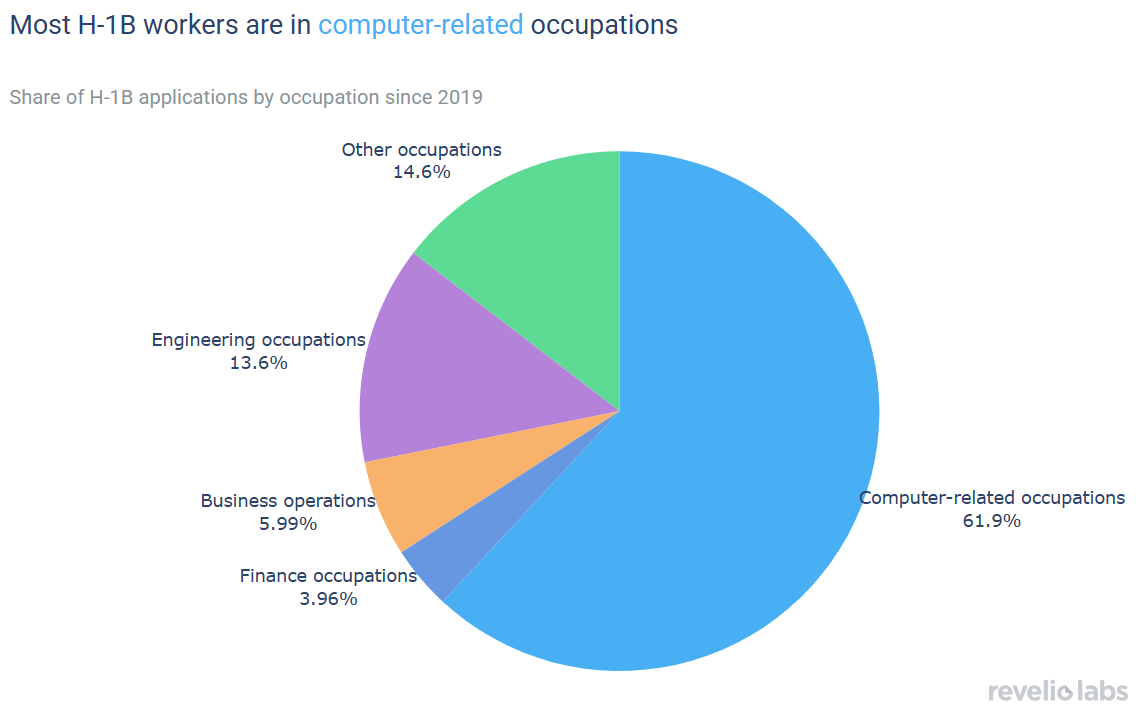

Since 2021, most H-1B applications have been for tech-related occupations, accounting for about 62% of all filings, followed by engineering and mathematical sciences at around 13%. This reflects the U.S. economy’s rising demand for tech talent amid the boom in software, cloud computing, and AI. The trend also mirrors broader shifts in education. Over the past decade, the share of foreign students in U.S. universities has increased, with many pursuing degrees in computer science, engineering, and other quantitative fields.

The H-1B program requires petitioners to demonstrate that the wages they pay their employees are at least equal to the prevailing wages in their respective occupation and local labor market. This Labor Certification Approval (LCA) process ensures that H-1B wages are on par with non-visa wages. When we compare the average salaries by occupation in H-1B petitions to those from new job postings, we find that across all occupations, salaries in LCA applications are higher than salaries in job postings, reflecting that foreign workers negotiate salaries for employment in a similar manner to American workers.

The H-1B visa system plays a critical role in allowing U.S. companies to access global talent, but it has long faced criticism for inefficiencies, inequities, and outdated rules. While reform is undoubtedly needed, raising application costs nearly tenfold is not the solution. Raising the application costs does not address the system’s structural problems; rather it acts as a tax on employment that creates new challenges for both employers and skilled foreign workers. Below, we highlight key reasons why raising the cost of H-1B applications is unsound policy.

First, raising H-1B fees so dramatically is effectively equivalent to dismantling the H-1B system, potentially eliminating up to 140,000 new jobs per year—about 10,000 per month—in U.S. companies that depend on skilled foreign talent. While the administration argues this will create jobs for Americans, there is little evidence these roles would be filled by U.S.-born workers, who are often scarce in these specialized fields. Moreover, although unemployment has increased slightly over the past year, it remains very low by historical standards, meaning there are relatively few skilled Americans unable to find work. Beyond the workplace, H-1B workers contribute substantially to the U.S. economy through consumption, housing, and community participation, often bringing families who generate additional economic activity. Eliminating or reducing H-1B employment could therefore have ripple effects, slowing economic growth rather than addressing the structural issues within the visa system.

Companies may seek ways to offset these rising costs, such as adapting remote work which enables them to hire international workers remotely, or relocate their operations to other countries where high quality talent is more accessible. As noted above, 60% of H-1B petitions are for tech workers, whose jobs are highly suitable for remote work, making this a highly viable option for many firms. Nicole Baynham, Head of Partnerships at MobSquad, noted that since the announcement, numerous companies, immigration attorneys, and technology professionals have reached out to inquire about how MobSquad can help U.S. firms maintain access to critical technology professionals from Canada. In practice, the prohibitively high fee is more likely to push jobs offshore than to boost domestic employment.

Second, raising H-1B application costs acts as a distortionary tax on employment, driving up the price of skilled labor in the U.S. and significantly hurting firms. A company in need of specialized talent faces two distorted choices: hire a foreign worker and pay both their salary (potentially suppressed) plus the inflated application fee, or hire a U.S.-born worker at a wage that reflects this added cost. In competitive labor markets, wages tend to equalize; otherwise, arbitrage opportunities would emerge. For instance, if the going salary for a data scientist is $150,000, the policy prevents a firm from hiring a foreign worker at that rate. Instead, the firm might suppress the wage to $90,000 and add $100,000 in H-1B fees, effectively paying $190,000. In turn, it would need to pay an American worker roughly the same amount. The outcome is not more jobs for the U.S.-born workers, but higher labor costs across the board. Rather than creating opportunities for Americans, the policy makes hiring skilled talent more expensive and undermines the global competitiveness of U.S. companies.

Furthermore, small companies and startups are likely to be disproportionately harmed by the new H-1B fees. Unlike large, established firms that can absorb or pass on added costs, early-stage companies often operate on thin budgets and limited revenue. For them, the new fees function as a direct tax on employment, even before they generate taxable income. This burden limits their ability to hire the skilled talent, stifles growth, and slows innovation. By tilting the playing field toward bigger firms with deeper pockets, the policy risks consolidating the tech sector and creating anticompetitive effects.

Third, dismantling the H-1B system risks accelerating brain drain from the United States. The country invests heavily in postsecondary education, and hosts the largest share of the world’s top-ranked institutions. In the past four years alone, the share of foreign-born students at U.S. universities has increased by one-third, making international talent increasingly central to America’s higher education system. Many of these graduates rely on the H-1B program to enter the workforce, and contribute to U.S. innovation. Importantly, foreign graduates do not necessarily earn a large salary premium compared to their U.S.-born peers, making the new $100,000 fee especially discouraging. Rather than retaining top global talent, the United States risks pushing them toward competitor countries eager to attract skilled workers, weakening America’s long-term innovative edge.

A further risk of dismantling the H-1B system is its impact on American innovation. Our previous research using U.S. patent data shows that foreign-born workers play a critical role in driving technological progress and productivity. In fact, foreign-born inventors in the U.S. are more productive than their native-born counterparts, producing 1.6 more patents on average for U.S. firms. Many of these innovators first arrived in the United States as international students, trained at leading American universities and then transitioned into the workforce through the H-1B program. By discouraging skilled graduates and inventors from staying, the new $100,000 fee threatens to slow the pace of innovation, undermining one of the key drivers of U.S. global competitiveness.

Fourth, the new H-1B fee structure also risks widening wage inequality among high-skilled workers. As companies become less able to sponsor new foreign workers and existing H-1B holders face barriers to changing employers, career mobility for skilled international talent will be constrained. In response, equilibrium wages may rise, but unevenly: firms will bear the higher cost of hiring new talent, while visa holders who are effectively “locked in” to their current employers may see slower wage growth compared to their non-visa peers. The result is a growing take-home pay gap between visa and non-visa workers, as the overall cost to companies remains elevated.

Immigration policy is a cornerstone of economic competitiveness. Access to global talent strengthens America’s position on the world stage, while shutting it out risks erasing the U.S. from it. Talent is not just a complement to the U.S. economy, it is a must-have. Pricing out talent for U.S. employers will not create more jobs for Americans; instead, it will push companies to find workarounds, such as relying on remote work and hiring more accessible talent abroad, or even relocating entire operations to other countries. Far from protecting U.S. jobs, such measures could ultimately eliminate them.

The H-1B system does need reform, but simply raising fees to a prohibitive level does nothing to address its flaws. Meaningful reform would update prevailing wage requirements to better reflect labor market conditions, tighten safeguards against fraud and abuse, and strengthen protections that allow workers to change employers more freely so that talent is more efficiently allocated. Such changes would preserve the benefits of the H-1B system while making it fairer, more efficient, and better aligned with the needs of the U.S. economy.