Europe’s Bid for PhD Talent Is No Match for US Private Dollars

The great PhD migration that Europe forgot to pay for

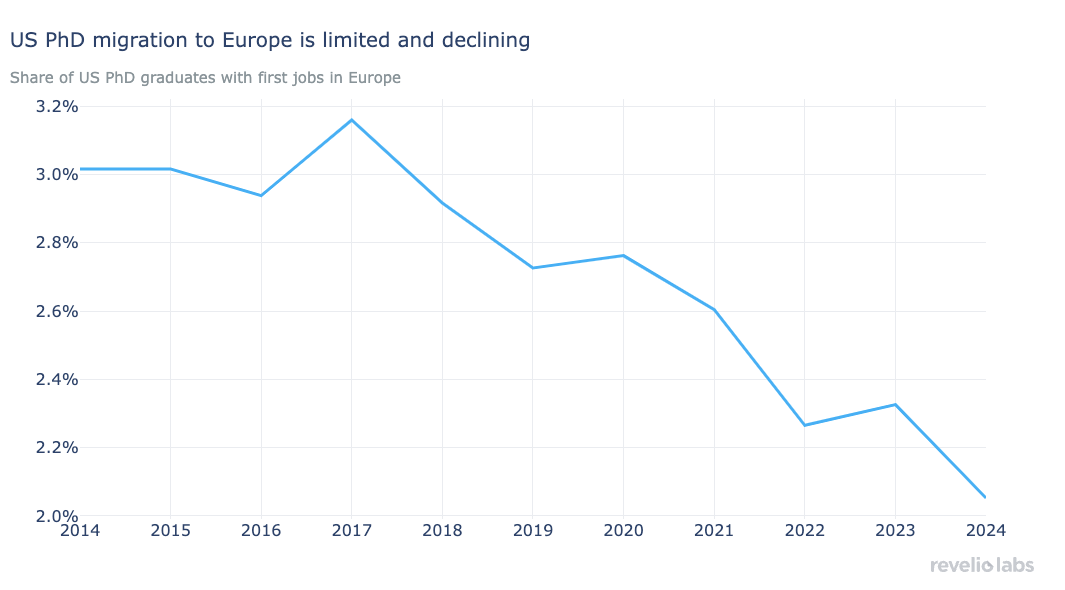

Despite policy shifts to attract more PhD-level talent, the share of US PhD graduates taking their first job in Europe continues to decline.

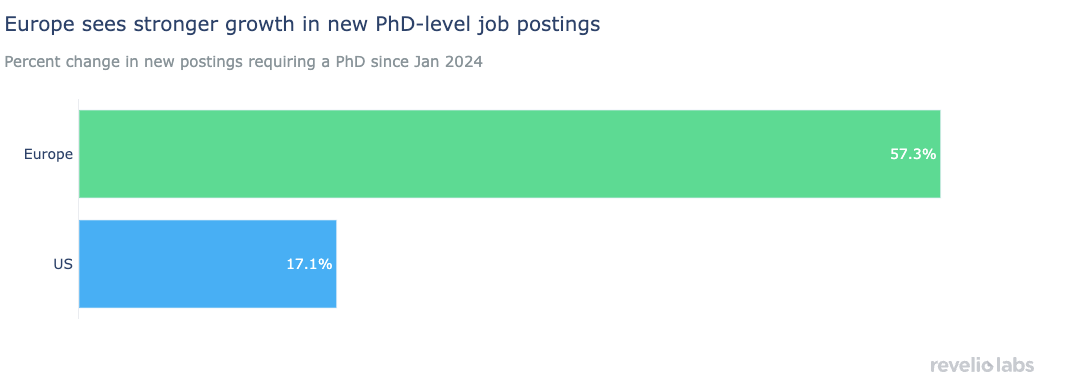

Europe has seen a recent spike in PhD-level job postings compared to the US, but lagging salary growth may limit its ability in attracting top US-educated talent.

In the US, salary growth is concentrated in the private sector while academic pay has stalled, pushing more PhD graduates into non-postdoc research roles outside universities.

Federal research funding in the United States has come under pressure from recent cuts, raising concerns about the stability of academic career paths for PhD graduates. At the same time, Europe is intensifying its efforts to attract researchers, positioning itself as an appealing destination through expanded opportunities and favorable policies. These diverging trends are reshaping the global landscape for scientific talent and influencing where the next generation of researchers may choose to build their careers. In this week’s newsletter, we take a closer look at the job choices of recent US PhD graduates and assess whether Europe is emerging as a viable alternative.

Despite Europe’s efforts to attract research talent, the share of US PhD graduates taking their first job in Europe has declined in recent years, suggesting that graduates are not moving there in meaningful numbers. However, the trend does not yet reflect the most recent policy changes, and it may take more time to see whether Europe’s initiatives translate into tangible gains in drawing talent from the United States.

However, when we look at the change in new postings, we see a recent spike in the growth of openings requiring PhD degrees in Europe compared to the US. This suggests that Europe’s efforts to attract PhD talent are beginning to show up on the demand side. Whether this increased demand will ultimately translate into more US PhD graduates pursuing careers in Europe remains to be seen.

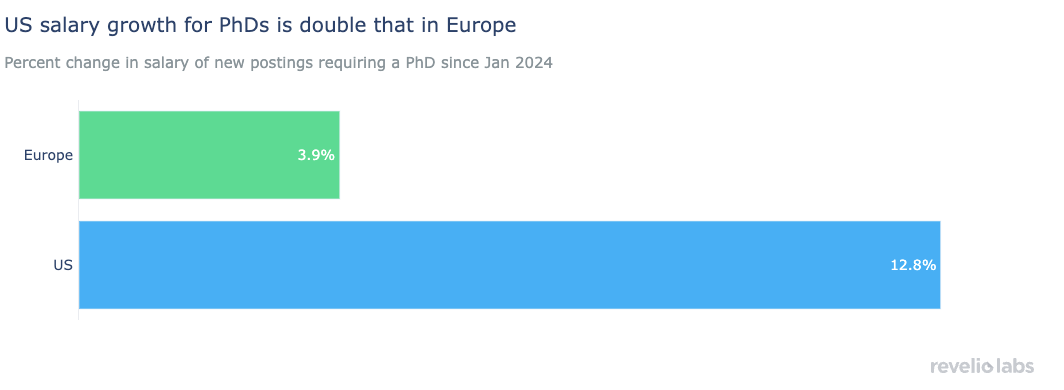

One factor that could limit such migration is compensation. Although the volume of new postings has increased much more in Europe, salary growth in these openings is lagging. Average pay in Europe has risen only from $60,000 to $62,500 since Jan 2024, compared with an increase in the US from $91,400 to $103,000. This disconnect suggests that while demand for PhD-level talent is rising, compensation is not keeping pace. As a result, the European job market may appear less attractive to highly skilled researchers, particularly when compared with opportunities in the US where salary growth has been stronger. Without competitive pay, Europe’s ability to convert higher demand into actual hiring of top talent could remain limited.

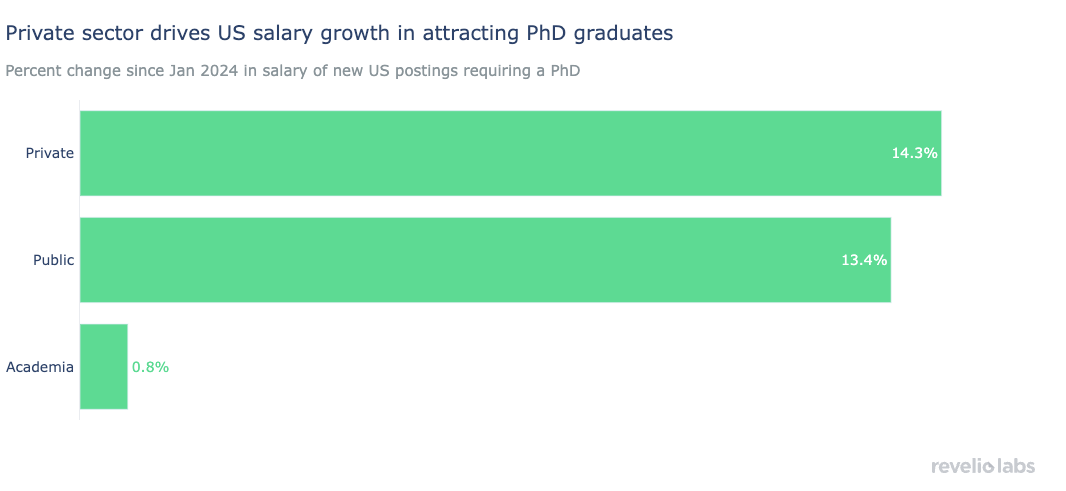

For PhD graduates considering career paths in the US, there is a clear divide in salary trends between sectors. The strong salary growth in the US is being driven by the private sector, while pay in academia has stalled. For researchers affected by funding cuts within US universities, the private sector may increasingly become the first option—especially when contrasted with Europe, where salary growth in new PhD-level postings has been much slower overall.

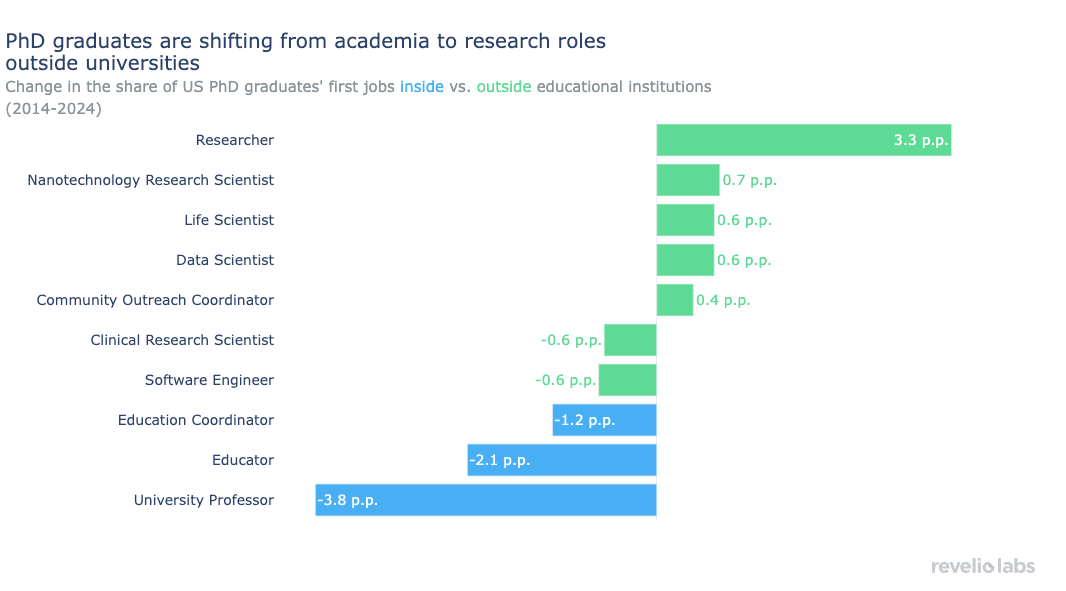

The trend of leaving academia for research roles outside universities has been evident for the past decade. Looking at the job breakdown of US PhD graduates’ first positions between 2014 and 2024, an increasing share are entering non–postdoc researcher or scientist roles outside the university setting, rather than faculty positions within universities and other educational institutions. This shift reflects both the limited availability of tenure-track positions and the growing opportunities in industry research. It also highlights how career pathways for new PhDs are diversifying, with fewer graduates viewing academia as the default destination.

These patterns suggest that the global market for PhD-level talent is in a period of transition. Europe is signaling greater demand through new postings and policy initiatives, but unless compensation keeps pace, it may struggle to attract graduates in large numbers from the US. Meanwhile, within the US, the growing divide between academia and the private sector is steering more researchers toward industry roles. How these dynamics evolve will determine whether Europe can position itself as a true alternative for US PhD graduates—or whether the private sector in the US will remain the dominant destination for emerging research talent.