65 and Still Clocking In

Older workers are refusing to retire, younger workers are struggling to be hired

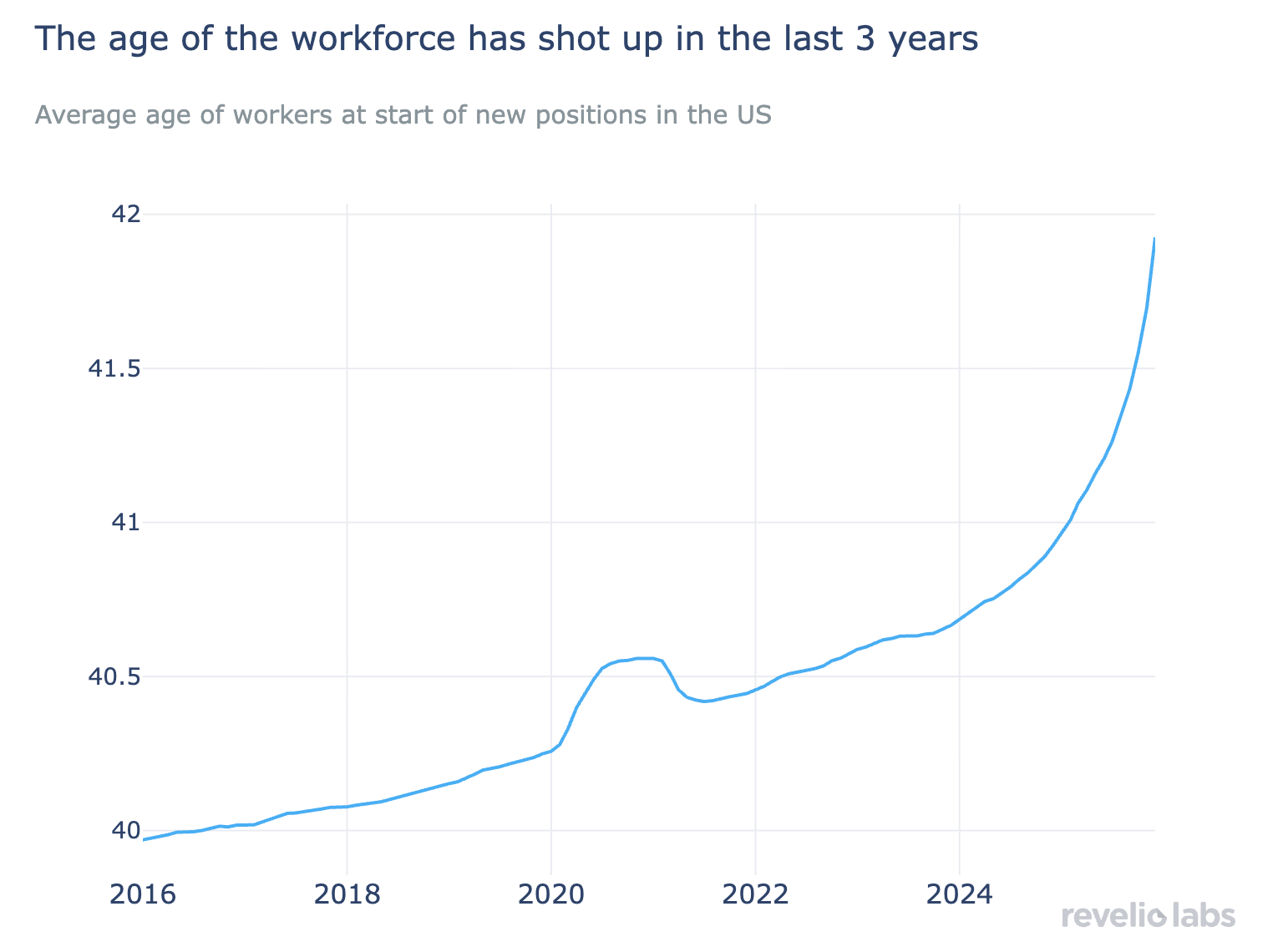

The average age of workers starting new positions has risen sharply since 2022 as older workers re-enter or remain in the labor market and younger workers face fewer entry opportunities. This pattern is consistent with a labor market that is slowing, becoming more selective, and prioritizing experience over long-term potential.

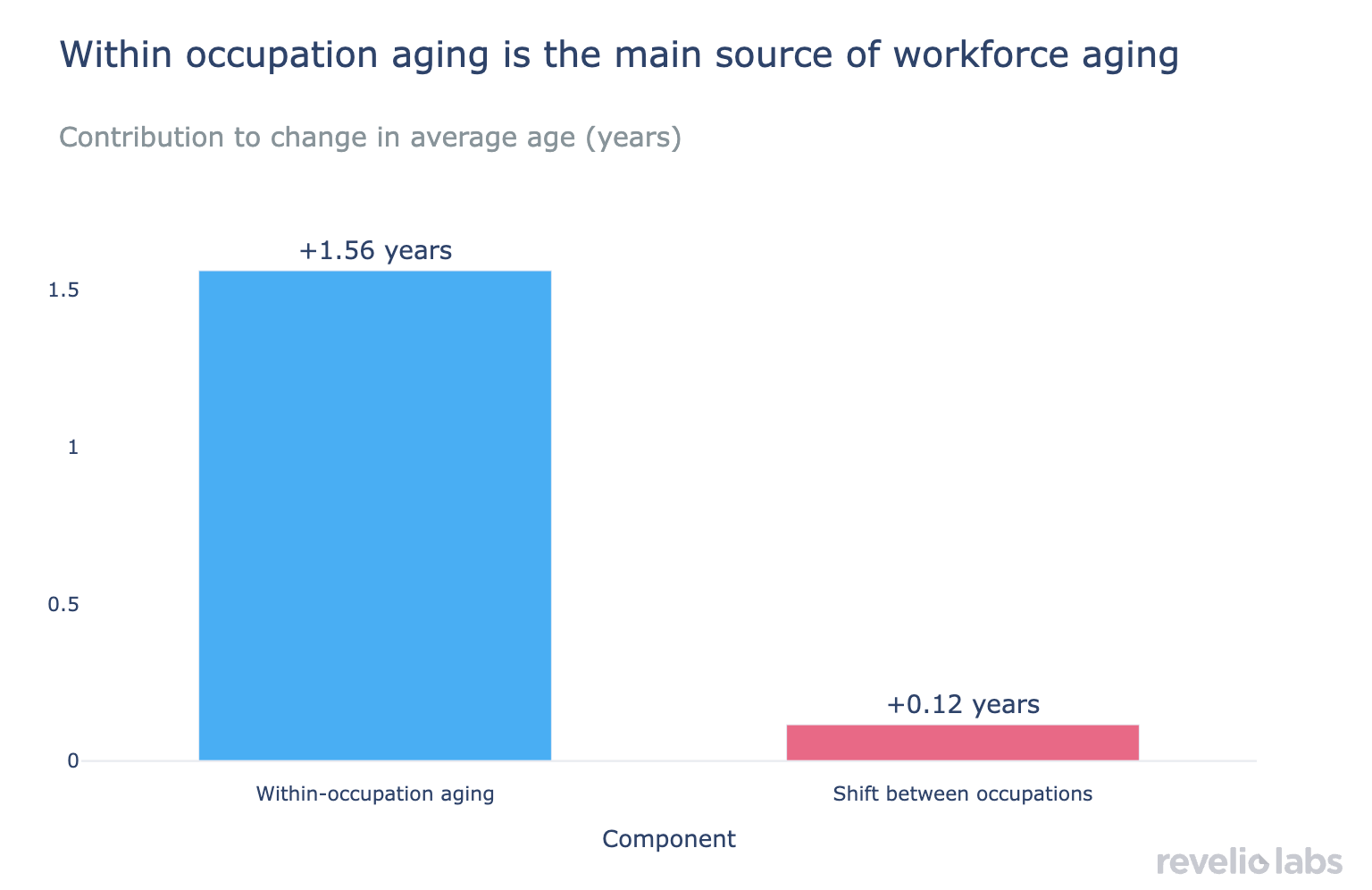

Workforce aging is happening almost entirely within occupations, driven by delayed retirements and weaker entry-level hiring, rather than by a shift toward industries or roles that inherently skew older.

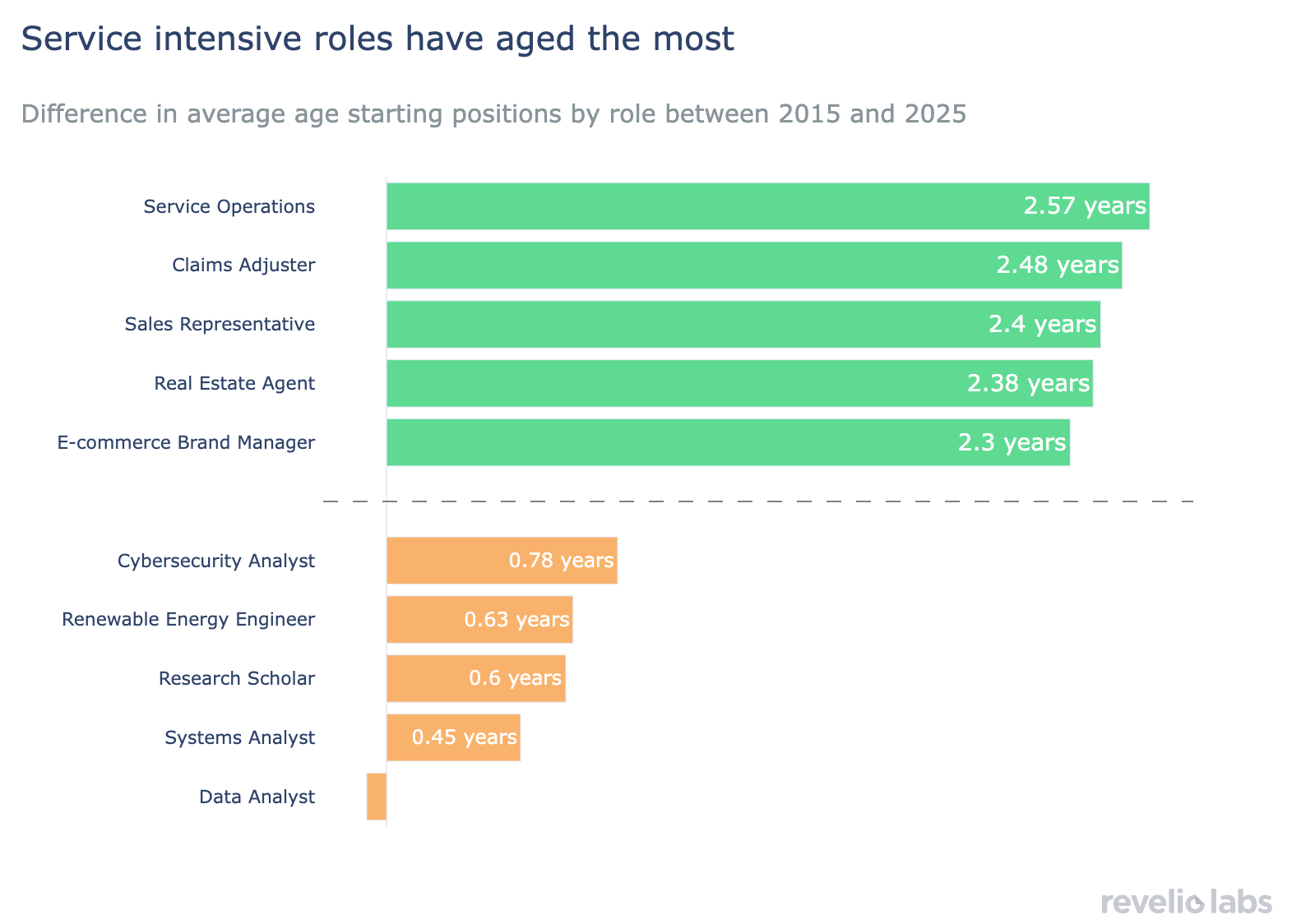

Service-intensive and people-facing jobs are aging the fastest, reflecting greater emphasis on experience, judgment, and networks over formal credentials or early-career potential.

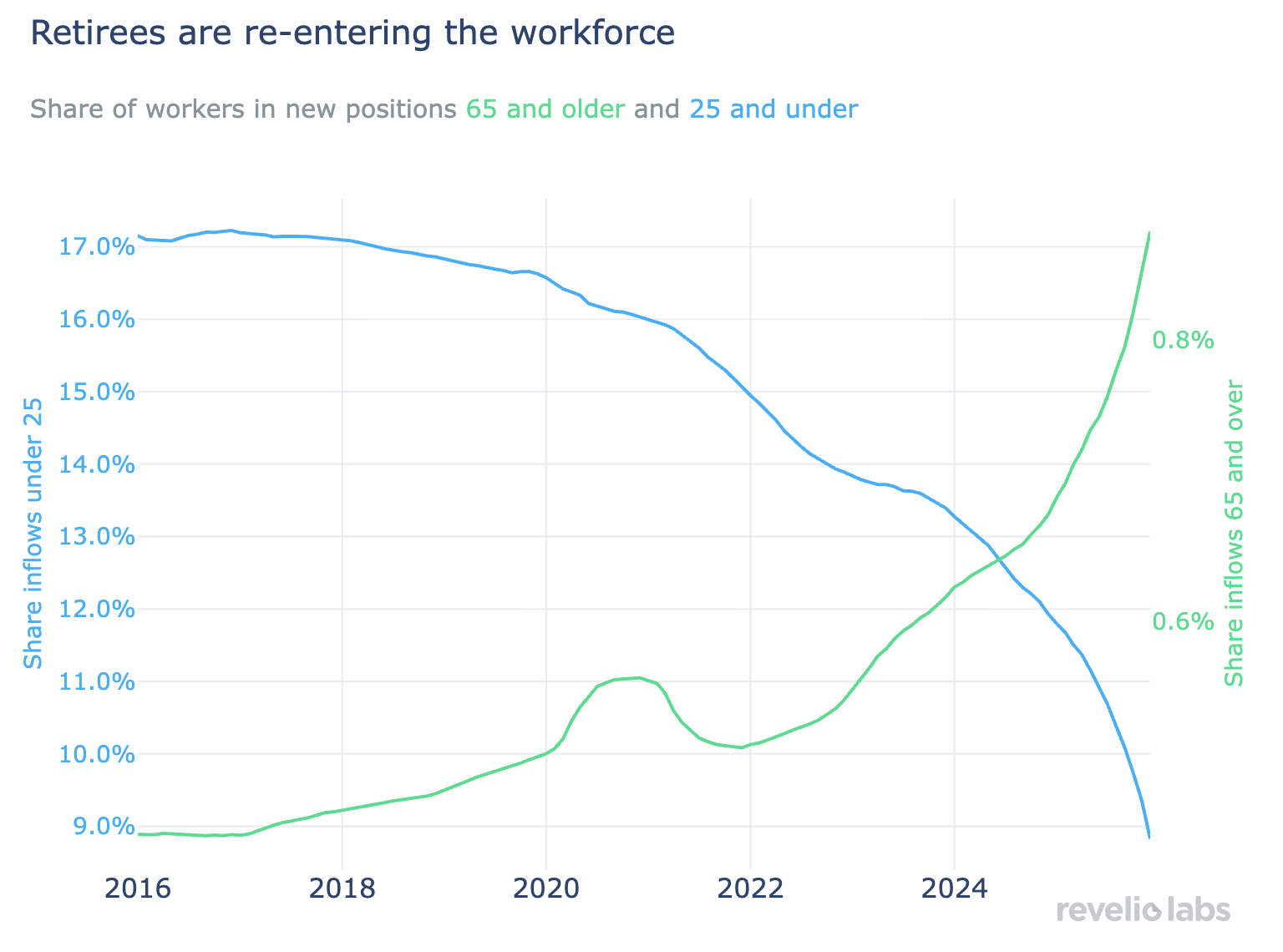

The share of workers under 25 starting new positions in the labor market has been declining steadily since the mid-2010s, falling from around 16% to single digits by 2025. Over the same period, with a marked acceleration after 2022, the share of workers aged 65 and older entering new roles has risen sharply. These opposing trends now define who is actually moving into new jobs in today’s labor market.

This shift is often framed as a demographic inevitability, but the timing suggests something more cyclical in nature. The renewed inflow of older workers coincides with higher interest rates, slower hiring, and a pullback in employer risk-taking. When growth is abundant, firms are more willing to hire for potential and train workers on the job. When growth slows, hiring does not disappear; it becomes more conservative. Experience, immediate productivity, and role readiness suddenly begin to matter more, making older workers comparatively attractive.

The change is visible in the average age of new hires. After rising gradually for years, the average age at position start increased sharply after 2022, reaching over 42 years old by 2025. This is the opposite of what typically happens late in an expansion, when tight labor markets pull younger workers into new roles and lower the average age of hires. Instead, the current cycle shows a labor market that remains active but is increasingly tilted toward experience.

A decomposition of the change in the average age makes clear that this is not a story about the economy reallocating toward occupations that skew older. Nearly the entire increase, for just over two years, comes from aging within occupations. Shifts between occupations contribute very little. In practice, this means that the same jobs are being filled by older workers than in the past, rather than new jobs emerging that inherently require older employees.

Sign up for our newsletter

Our weekly data driven newsletter provides in-depth analysis of workforce trends and news, delivered straight to your inbox!

That pattern is mechanically consistent with two forces operating simultaneously: fewer young workers entering the labor market and fewer older workers exiting it. Entry-level hiring has weakened across much of the economy, while older workers have become more willing to stay in the labor force or return after retirement. Together, those forces raise the average age even if the underlying occupational composition barely changes.

The roles experiencing the most pronounced aging further reinforce this interpretation. Service-intensive and people-facing jobs have aged the fastest since 2015. Service operations, sales representatives, claims adjusters, office assistants, and real estate agents have all seen average ages rise by close to three years. These are roles where accumulated experience, interpersonal skills, and institutional knowledge are central to productivity—and where performance does not depend on keeping up with rapidly changing technical toolkits.

By contrast, more technical and analytics-driven roles have aged far less. The average age of data analysts has declined, and systems analysts have only seen modest increases in average age, reflecting the continued importance of formal training pipelines and early-career hiring in these fields. The result is a growing divergence across occupations in who gets hired, not because of structural shifts in labor demand, but because hiring incentives have shifted.

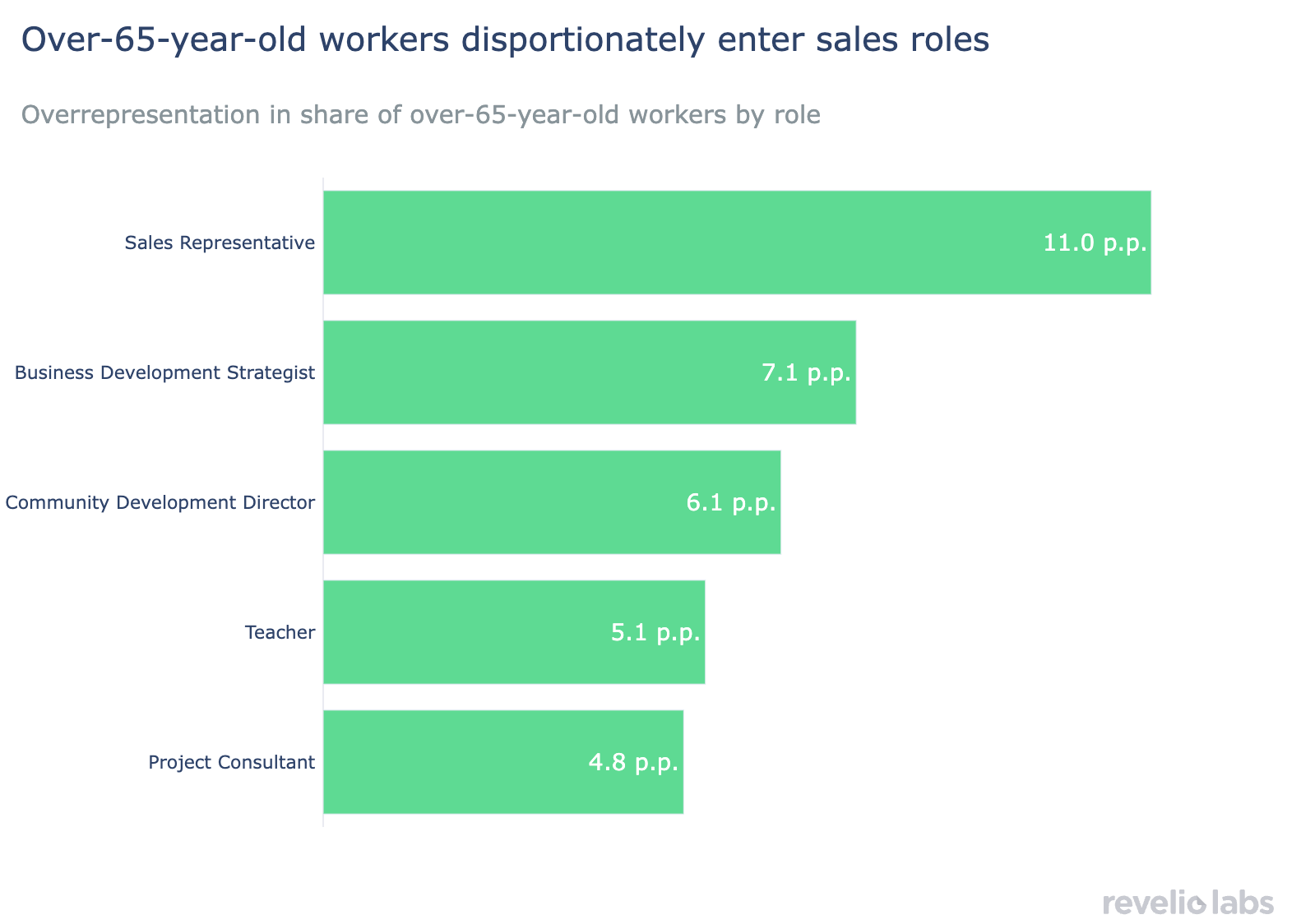

Older workers are also not re-entering the labor market at random. Workers over 65 are disproportionately starting new roles in sales, strategy, community-facing, and teaching positions. Sales representatives stand out in particular, with workers over 65 overrepresented by more than ten percentage points relative to other age groups. These roles reward credibility, judgment, and networks. Such qualities compound over time and often offer flexible arrangements that make re-entry more appealing later in life.

Taken together, the data point to a labor market that is aging not simply because the population is getting older, but because economic conditions have changed. Slower growth, tighter financial conditions, and higher hiring thresholds have reshaped who gets opportunities and at what age. Older workers are staying longer in the labor force or returning from retirement, while younger workers face higher barriers to entry. The result is a workforce that looks older, turns over less, and blurs the once-clear line between working life and retirement.