Was 2025 Really the Worst Year To Graduate?

Graduates faced a tough labor market, but previous cohorts can relate

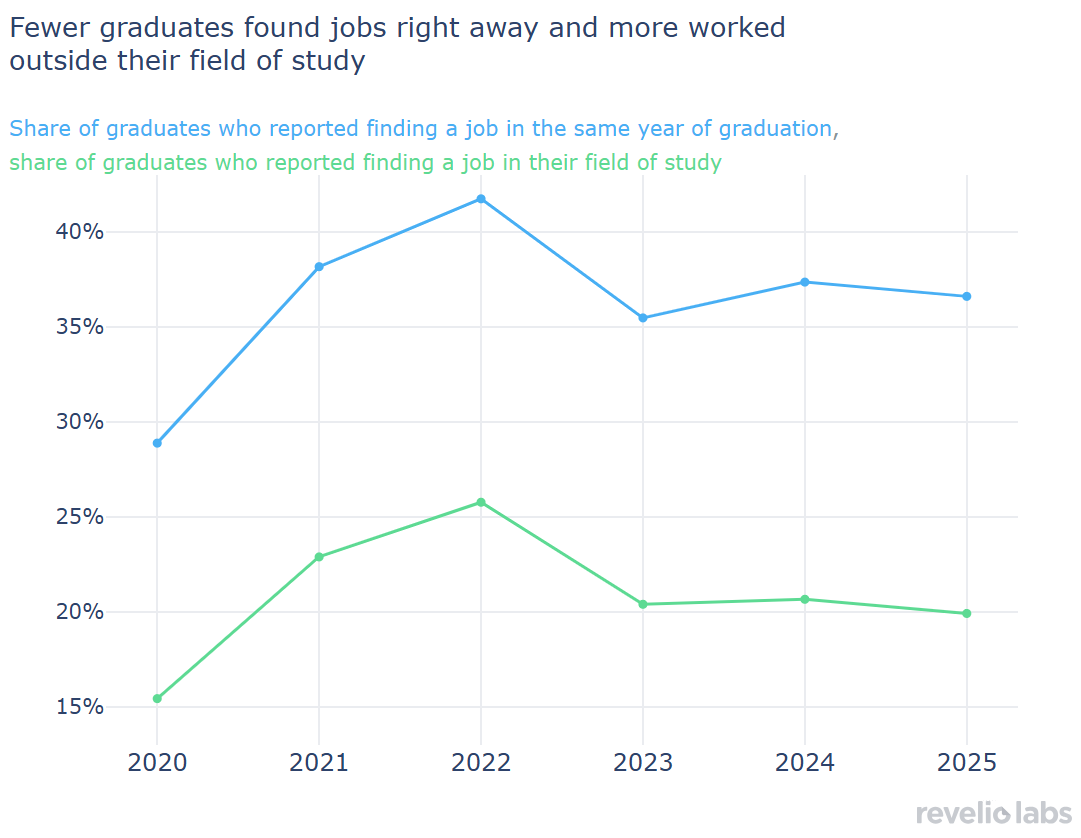

Graduate entry-level employment is shrinking, but the class of 2025 is not unique in its struggle. The share of Bachelor’s graduates reporting starting a job in the same year of graduation has been declining since the 2023 cohort as the post-pandemic hiring surge receded and entry-level labor demand cooled.

Furthermore, the job match quality is deteriorating. The share of graduates who reported finding a job that aligns with their field of study immediately after graduation has been declining as entry-level opportunities narrow.

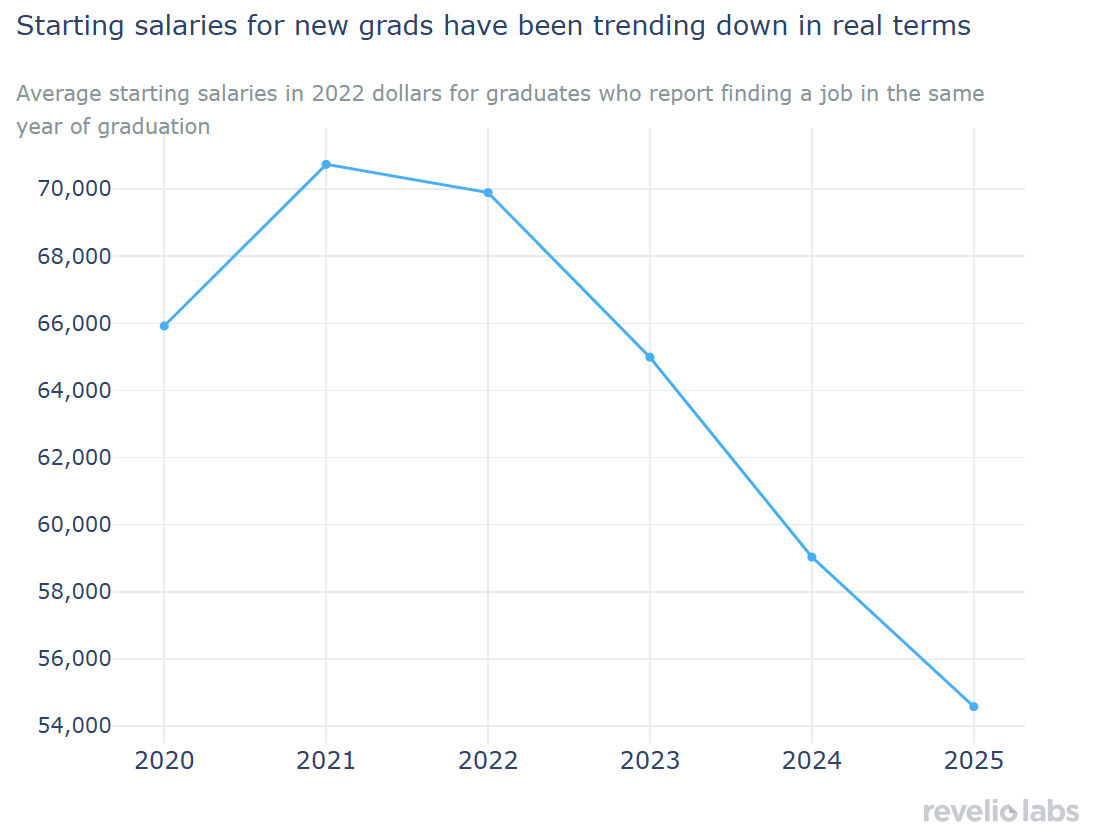

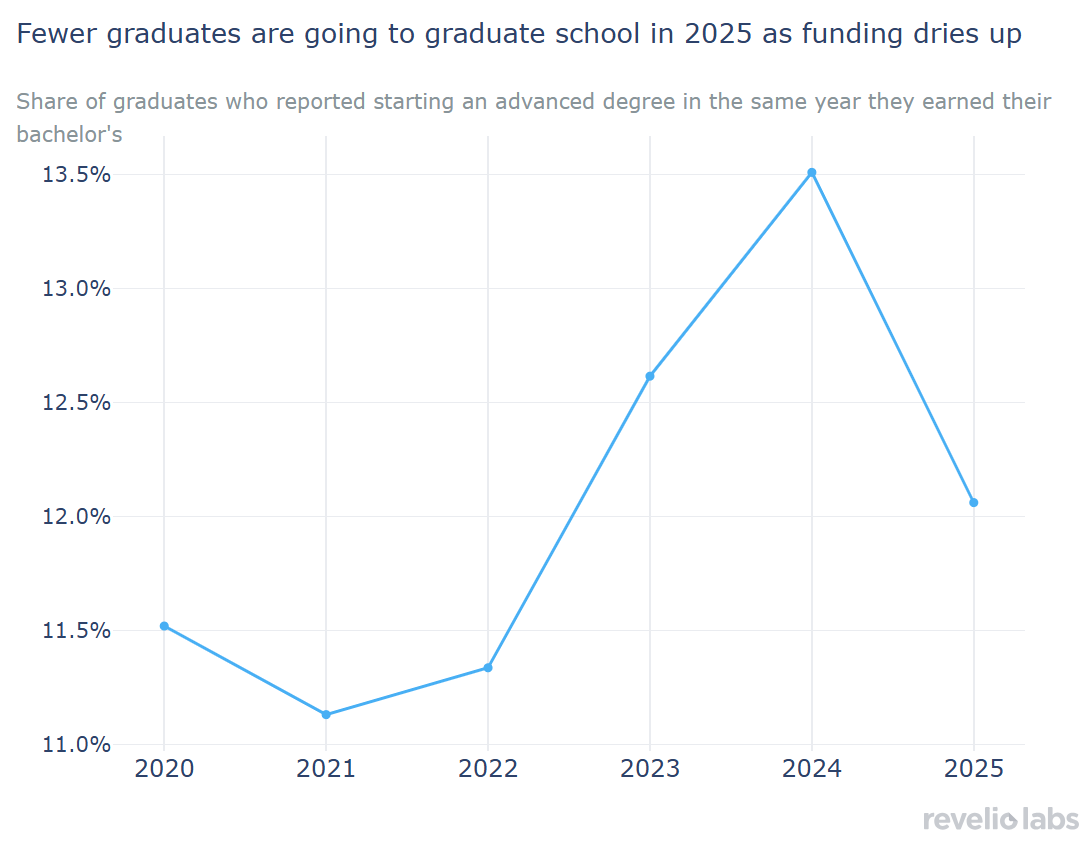

The payoff to education at labor market entry is also weakening. Inflation-adjusted starting salaries have dropped down to their lowest level since 2021, consistent with graduates being pushed into lower-paying or less degree-relevant roles. At the same time, more graduates are delaying labor market entry altogether as grad school enrollment in the same year of graduation has been rising steadily since 2023.

One of 2025’s main headlines that sparked a national conversation was that the 2025 cohort of college graduates is struggling to find employment. As the labor market has been cooling off over the past two years, headline unemployment remained stable while the entry-level labor market has shown clear signs of stress. In earlier work, we documented the decline in entry-level job openings since 2023, suggesting that the first step of the career ladder is weakening. We have also shown that the share of workers under 25 starting new positions has been declining steadily. In this newsletter, we ask what this shift means for the cohorts graduating into today’s market: How difficult has the transition from college to work been for the class of 2025? And are these challenges unique to the 2025 cohort, or are they part of a trend that started earlier?

Using Revelio Labs’ worker-level data, we track college graduates who reported starting a job in the same year they earned their bachelor’s degree. To be able to make apple-to-apple comparisons and avoid issues of reporting lag, we focus on the subset of graduates who report their degrees in the same year they earn them.

First, we observe a clear decline in the share of Bachelor’s graduates who report starting a new job in the year they graduate. For the 2025 cohort, about 36.6% of graduates report both receiving a degree and starting a job within the same year. Importantly, the low share of graduates who report finding a job in the same year of graduation is not unique to the 2025 cohort: the fall began with the 2023 cohort, the first to enter the labor market after the post-pandemic hiring surge began to fade. As labor market conditions cooled and entry-level hiring demand returned to normal, fewer new graduates transitioned directly from graduation into employment. This trend is consistent with weaker entry-level hiring conditions and the rise in unemployment among younger workers, and particularly recent college graduates, which started in mid 2023.

The decline in the share of new graduates starting a job in the same year as their graduation has been mirrored by a parallel drop in field-to-job alignment. As shown in the figure above, the share of recent graduates whose first job aligns with their degree has fallen from over 25% in the 2022 cohort to roughly 20% for the 2025 cohort. While most Bachelor’s degree holders still begin their careers in white-collar roles, the downward shift in alignment of jobs with fields of study points to a growing mismatch between graduates’ training and the jobs available to them. Although early-career matches are never perfect, the pattern suggests that cohorts entering a cooling labor market are increasingly settling into roles outside their field of study, prioritizing speed over fit in a weaker entry-level environment. It’s not just harder to find a job quickly; it’s also harder to find the right job.

The growing mismatch between fields of study and entry-level job opportunities has clear implications for salaries. Many students choose their degree fields in college partly based on expected career paths and earnings potential. When graduates are pushed into roles outside those pathways, the return of education at labor market entry weakens. After peaking around the 2021 cohort, real starting wages have fallen steadily, with the 2025 cohort earning the lowest starting salaries in inflation-adjusted terms. In other words, the entry-level labor market has softened not only in hiring, but also in wage offers. Even graduates who do land jobs are seeing their starting pay fall further behind inflation.

One potential response to weaker entry-level hiring conditions is continued schooling. In economic downturns, enrollment in education typically rises as the opportunity cost of school declines when suitable jobs become harder to find. The share of Bachelor’s graduates who report starting graduate school in the same year as graduation has increased notably since 2023, consistent with the idea that some new graduates delay labor market entry and invest in additional education instead. Over time, this share rose from under 11% in 2020 to above 12% in recent cohorts, peaking in 2024. However, the pattern is not purely monotonic: the share remains elevated in 2025 but falls below the levels observed in 2023 and 2024. One possible explanation is the current U.S. administration’s cuts and the resulting uncertainty around university and research funding. These factors have made it harder for graduate programs to support incoming students, limiting enrollment even as labor market incentives to stay in school remain strong.

Early-career outcomes are an indicator of the broader labor market health. The decline in entry-level opportunities is not unique to the 2025 cohort: the decline in smooth school-to-work transitions and degree-aligned placements began with the 2023 cohort, as the labor market cooled after the post-pandemic hiring surge. When graduates struggle to secure degree-relevant roles, the cost is not just short-term unemployment, underemployment or lower pay, but lost early-career momentum that can compound for years. Graduates taking jobs outside their field or delaying entry with further schooling can make the labor market look stable on the surface, even as declining match quality quietly creates risks of long-term scarring.

For employers, this shift acts as an opportunity: a softer entry-level market expands the pool of well-suited candidates, but only for firms willing to hire earlier and invest in training entry level workers. For universities and policymakers, the message is equally clear: strengthening school-to-work pathways, expanding paid internships/apprenticeships, and protecting early-career workers should be treated as core workforce infrastructure.